Mistaken Identity

Crane fly

Crane flies, also known as mosquito eaters, and mosquito hawks.

Despite their common name, crane flies do not prey on mosquitoes as adults, nor do they bite humans.

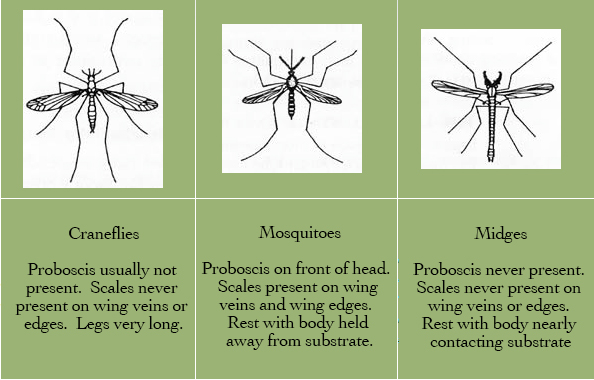

Adults are very slender, long-legged flyers that may vary in length. Smaller species are mosquito-sized, but they can be distinguished from mosquitoes by the V-shaped suture on the thorax, non-piercing mouthparts, and a lack of scales on the wing veins.

Some larval (immature) crane flies may on occasion feed on mosquito larvae but they do not feed on adult mosquitoes. Adult crane flies feed on nectar or they do not feed at all; once they become adults, most crane fly species only live long enough to mate and die.

Midge

Midges are non-biting flies that resemble mosquitoes in size and general appearance. They are approximately a half-inch in length and light green to brown in color.

They develop and breed in aquatic habitats similar to mosquitoes. Residents living near reservoirs, lakes, ponds, and flood control channels are frequently annoyed by midge swarms.

Midges are usually a problem from April to September and survive the winter as larvae in mud and at the water bottom. Swarms usually emerge at sunset.

Gnat

Adult gnats do not bite humans yet are often considered a nuisance. Gnats are dark, delicate-looking insects, similar in appearance to mosquitoes. They have slender legs with segmented antennae that are longer than their head. They are relatively weak fliers and are not often found flying around indoors. They generally remain near potted plants and organic debris.

Gnat larvae have a shiny black head and an elongate, legless body. They feed on moist organic debris such as leaf mold, grass clippings, compost, and fungi.

The adult males often assemble together in large mating swarms, particularly at dusk.

Mosquito Biology

Mosquitoes (Order Diptera, Family Culicidae) are some of the most adaptable and successful insects on earth and are found in some extraordinary places. Virtually any natural or man-made collection of water can support mosquito production. They’ve been discovered in mines nearly a mile below the surface, and on mountain peaks at 14,000 feet, and if you know where to look, there is a good possibility that there are mosquitoes breeding in your own backyard. Not every species of mosquito causes problems for people, but many have profound effects. Mosquitoes can be distinguished easily from other flies by the fact that they have both a long, piercing proboscis and scales on the veins of their wings. Approximately 176 species of mosquitoes belonging to 13 genera are found in the United States.

The Mosquito Lifecycle

Around 90% of the adult mosquito population in Montana is made up of two species, depending upon habitat. The first, and most vicious biter, is the “floodwater” mosquito, Aedes vexans. This mosquito and other closely-related floodwater species are responsible for nearly all severe outdoor annoyance. The second, an important disease vector, is Culex tarsalis. These two species, along with all other mosquitoes, must have water for their early stages, and all undergo the same four-stage life cycle: egg, larva, pupa, and adult. The larval and pupal stages are always aquatic.

Mosquito Eggs

Depending on the particular species, the female mosquito lays her eggs either individually or in attached groups called rafts. The eggs are placed either directly on the surface of still water, along its edges, in tree holes, or in other areas that are prone to flooding from rain, irrigation, or overflow. In some species, the eggs may hatch within a few days of being laid, with the exact amount of time dependent on temperature. But if the egg is laid out of the water and is subject to intermittent flooding, the embryo may lay dormant for many years until the ideal natural hatching conditions are met. Mosquitoes frequently overwinter in the egg stage, but may also overwinter as larvae or adults.

The Larval Stage

Once the egg hatches, the larval stage begins. The larvae of most mosquito species hang suspended from the water surface. An air tube extends from the larva’s posterior to the water surface and acts as a snorkel. The larvae filter-feed on aquatic microorganisms near the surface. As a defense mechanism, when alarmed, the larvae can dive deeper into the water by swimming in a characteristic “S” motion. As they feed, larvae outgrow their exterior covering and form a new larger skin, casting off the old ones. The stages between these molts are called instars. The larval stage has four instars. The length of the larval stage ranges from 4 to 14 days, varying with species, water temperature, and food availability.

The Pupal Stage

In the pupal stage, no feeding occurs. Like the larvae, the pupae are sensitive to light, shadows and other water disturbances. Pupae are also physically active and employ a tumbling action to escape to deeper water. The pupal stage lasts from 1 1/2 to 4 days, after which the pupa’s skin splits along the back allowing the newly formed adult to slowly emerge and rest on the water surface until taking flight.

Adult Mosquitoes

The male mosquito will usually emerge first and will linger near the breeding site, waiting for the females. Mating occurs quickly after emergence due to high adult mortality rates. As much as 30% of the adult population can die per day. The females compensate for this high rate by laying large numbers of eggs to assure the continuation of the species. Male mosquitoes will live only 6 or 7 days on average, feeding on plant nectars. Females with an adequate food supply can live up to 5 months, while the average female survives for a few weeks. To nourish and develop her eggs, the female usually must take a blood meal in addition to feeding on plant nectars. Females locate hosts by the carbon dioxide and other trace chemicals exhaled, and the temperature patterns they produce. Mosquitoes are highly sensitive to several chemicals including carbon dioxide, amino acids, and octanol. The average female mosquito’s flight range is normally between a few hundred yards and 10 miles, but some species can travel up to 40 miles before taking a blood meal. After each blood meal, the female will oviposit (lay) her eggs, completing the life cycle. Several ovipositions per female are possible.